Deeper Dive

Introduction

This page will help you explore the history, characters, and themes in Petlenuc Interrupted. It is designed to be explored after taking the tour, although some of the information here can help set up the story before you experience it.

If you are a teacher, see the Classroom Resources section at the bottom of this page.

Coyote’s Quiz

The “True” Story

What was “true” and what was made up in Petlenuc Interrupted?

This is a fictional story, written by screenwriters and creative journalists. But many of the facts and traditions presented were based on documented evidence we found in our research. Below is a stop-by-stop exploration of the facts behind the story as well as a closer look at the themes of the story.

-

The village of Petlenuc did exist in the area that we now know of as the Presidio. The name “Petlenuc” comes from the Ohlone name for the stream that ran through the area. We don’t know if the village was called “Petlenuc” by the people who lived there. As Helen says, it is important to avoid revealing the precise location of the village . If the exact location of the village sites were made public, people may trample or even raid sites that some Native Americans consider sacred. We aren’t certain how long the Ohlone lived on this site. Overall, there is evidence that native peoples inhabited the Bay Area for at least two millennia, and the ancestors of the Ohlone were in the Bay Area at least 4,500 years ago. (Cherny, Robert, A Short History of San Francisco, 2026.)

-

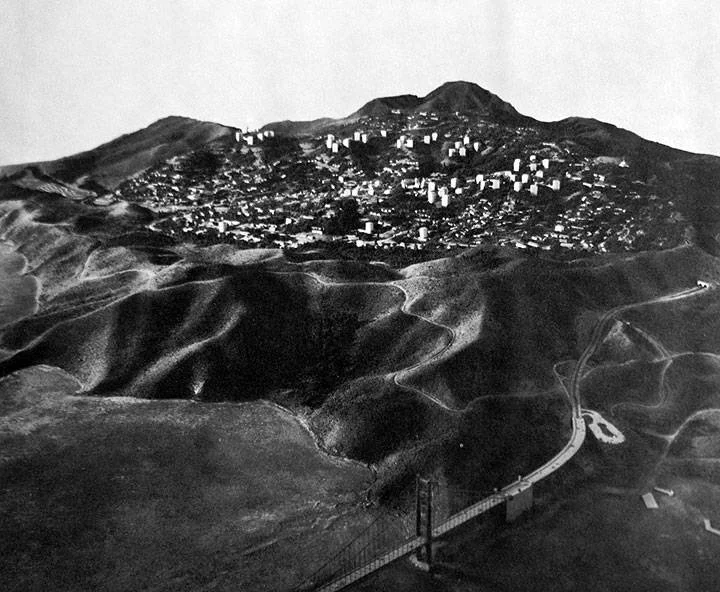

In this section Alfi notes that he’s walking between distant highrises and the Headlands of Marin. He feels that the city and nature are opposing forces and begins to question what divides human spaces from what we call nature. “Isn’t every space natural, in a way?” he asks. This question of what nature is and how modern people can get closer to it is a big theme in this story. Scholar and curriculum designer Beverly Ortiz notes, “Today, many modern people describe their own relationship with the land as living on the land. But the Ohlone peoples believed, and continue to believe, that people should live with the land.” (Margolin, Malcolm, The Ohlone Way, 2014) This integration of humans into nature, living “with the land,” respecting it, understanding its cycles is something Alfi is naturally curious about and trying to integrate into his modern life. He, like many of us, isn’t quite sure just how to get closer to nature. It’s a challenge that drives the story and Alfi’s evolving understanding of what it meant to live as an Ohlone.

As a side note, in the 1960s, the “natural” Marin Headlands Alfi is pondering were almost developed into a new, fancy suburb. It was going to be called “Marincello!” It’s an interesting story but I think we’re all glad it wasn’t built. It also brings up the consideration that preservation of natural landscapes isn’t what the Ohlone were doing exactly. The Ohlone cared for land not by leaving it untouched, but by tending it. They managed the flow of fish and even burned some plants to encourage the growth of others. This is explained in Kat Anderson’s article, “Native American Land-Use Practices.”

-

The village that appears in this chapter is designed to look like Minecraft because Helen is trying to gamify the app and make it appealing to kids. It doesn’t represent how Ohlone huts actually looked. However, the objects in the huts and their descriptions are true! Well, except for Helen’s guess about Ohlone shields. It's doubtful the Ohlone used shields, but that artifact fits with Helen’s intent to make Ohlone life seem like a life-and-death battle with nature. In fact, many of the objects hidden in the village are weapons. In reality, the Ohlone were skilled hunters, but rarely engaged in warfare. In his book The Ohlone Way, Malcolm Margolin points out, “Most of the time hostility was contained, always simmering under the more or less placid surface of daily life, but only rarely boiling over into the open.” The Ohlone were often bonded to surrounding tribes through marriage and so killing people from other tribes was close to fratricide. Most of the weapons featured in this chapter were for hunting and the Ohlone were excellent hunters. But the weapons were also considered sacred and were kept by the sweathouse, so you would never find them in a family’s hut, as depicted in Helen’s village.

Also, in this chapter we meet Coyote. Coyote comes out singing “The Barbie Song.” Now, of course this is not a traditional Ohlone song, but Coyote was traditionally funny and constantly did unexpected things. Coyote stories were often told to entertain people, especially in the cold, rainy months of the winter. A Coyote story could make everyone laugh and feel more connected. That is the intent of this story’s version of Coyote through the use of modern jokes and cultural references.

So, who is Coyote for the Ohlone? Well, he’s more than just a trickster. As Hendrick tells Alfi, “Coyote is a god, a child, an adult who does R-rated things!” This is all pretty accurate as many Coyote stories involve acts that would get an R-rating in our movie industry. But there is also an important spiritual and godhead role Coyote plays in Ohlone culture.

Some Native American scholars and tribal members don’t think Coyote should be called an animal god or a simple trickster. They prefer terms like “Coyote First Person.” This captures the concept that Coyote is not just a myth, but a real being who inhabited this world during the Sacred Time. He is the father of humankind and should be respected as such. More information on Coyote First Person and the various ways Native Americans view his character can be found in this article: “Coyote is not a metaphor: On decolonizing, (re)claiming and (re)naming Coyote.” -

This chapter explores the concept of shelter as not just the hut, but the entire ecosystem the Ohlone lived within. In contrast to Helen’s “Minecraft” huts, this hut includes various elements of the surrounding landscape. The goal of exploring this hut isn’t to collect objects and learn information, but to feel the connection the Ohlone had between their houses and nature. Coyote sings,

This was their home

Every blade of grass,

Stone, and drop of water

Not hut-dwellers

They were

World-dwellers

So no…

They didn’t survive.

In the world around us

They were,

They are

Fully alive

Nothing in Coyote’s hut is “realistic.” An Ohlone hut wouldn’t actually look like that. But the concept that they lived “with” nature, as Beverly Ortiz points out, is very realistic. For the Ohlone, even when you were indoors, you were outdoors. You can find more information on how the California indigenous people lived within nature in the article “Native American Land-Use Practices” by Prof. Kat Anderson. -

In this chapter, Coyote tells the story of how humans were created, starting with a great flood, which leaves Coyote stranded on Mt. Tam. Then with the help of Eagle, Hummingbird, and a squaw, Coyote figures out how to make humans. This story is an adaptation of various creation stories passed on by Bay Area indigenous tribes. In some stories, Mt. Diablo is where Coyote is stranded and for the Esselen tribe who reside near Big Sur, it’s Pico Blanco. In Petlenuc Interrupted, the Creation Story helps Alfi understand how important this place must have been to the Yalamu who lived here for centuries. “Wait, the whole world was created right here on the Bay?” Alfi asks incredulously. This chapter isn’t so much about whether this creation myth is true, but more about the true connection the Yalamu had to this land. The experience of seeing a place as the center of history, as the starting and ending point of your history and your lifetime was essential to the Ohlone experience. The degree of expertise humans get from such a focus on place cannot be understated.

This stop also introduces Alfi to the concept of Human Time and Sacred Time. The Ohlone believed that there was an era called Sacred Time that precedes human existence on Earth. In the Sacred time, the animals were believed to rule Earth like gods. The flood that brings on Human Time and banishes the animal gods from Earth is a feature of Ohlone beliefs and many other indigenous belief systems. According to Malcolm Margolin, this onset of a Human Time isn’t forever. The Ohlone believed this era would also come to an end: “Some time in the future this magnificent world, like the worlds before it, would be sapped of power. The people would eventually stop doing their dances and ceremonies, and the Ohlone world—their beautiful, living world—would collapse in upon itself and dissolve into chaos.” Thus the story Coyote tells Alfi at the end of the chapter about the end of Human Time does fit the Ohlone belief system. The concept that Coyote enlists a boy to stop this process and keep the world in human time is completely made up for the purposes of this story.

-

At this stop, Coyote asks Alfi to “Sweat your way to a solution.” The idea is that Alfi will experience a real Ohlone sweathouse where he will find visions and even “messages from the animal gods” to help him stop the cancellation of Human Time. This isn’t so realistic. While the sweathouse had the function of cleansing the body and the spirit, it wasn’t a quick process and wasn’t considered a direct line to the animal gods. The Ohlone would go to the sweathouse for hours, sometimes days in a row to prepare themselves for a hunt, dance, or other sacred ritual. Alfi’s rapid encounter with a vision has nothing to do with the long, arduous process of withstanding heat the Ohlone went through.

But the fact that the animal gods do offer something mysterious that Alfi has to interpret does fit with the Ohlone understanding of how the gods work. Malcolm Margolin notes in The Ohlone Way, “The Ohlones often sought out the animal-gods as helpers or advisors, but at the same time they were also deeply afraid of them. For these were still the animal-gods of the myths: amoral, unpredictable, greedy, irritable, tricky, and very magical.” The deer, badger, and eagle spirits Alfi encounters illustrate the type of the trickiness and struggle the Ohlone experienced when seeking advice from them. They also do a good job of embodying the hierarchy of natural objects the Ohlone believed in. Margolin explains, “Everything had power, but not equal power. A river stone had very little power of its own, while springs and rivers…had not only great power but great intelligence as well.” Thus the focus of Alfi’s vision on water, wind, and fire gets at the importance of these phenomena in Ohlone culture and sets up Alfi’s final discovery about how best to bridge this divide between humans and nature.

-

In the final scene of the walk, Alfi and the class gather around a campfire where Helen shows them an animation of various aspects of Ohlone culture they learned about. Alfi gets up the courage to interrupt Helen and point out that the Ohlone “didn’t use nature, they didn’t survive, they lived.” This is very true not just in the sense that the Ohlone didn’t see their lives as a struggle with nature, but also that they weren’t so different from us. They still joked, dreamed, married, and raised families. And many of the practices they had around spirituality, housing, and hunting were similar to what all of our ancestors did.

Alfi goes on to decode the sweat house vision as “having a conversation with nature. Eagle was trying to show me how to talk to the wind. Deer was showing me how to speak like flowing water. And Badger was showing me how to make words that ignite the world, like fire. It’s not something locked away in the past. It’s something we can all access.” This also falls in line with the Ohlone ideas of an animistic world, a world in which everything around you is alive and you’ve got to learn how to tune into it. As Malcolm Margolin describes it in The Ohlone Way, “The Ohlones, then, lived in a world perhaps somewhat like a Van Gogh painting, shimmering and alive with movement and energy...It was a basically anarchistic world of great poetry, often great humor, and especially great complexity. They shouted at the heavens not just to vent their fears, but because they thoroughly believed that if they yelled loud enough the thunder or the eclipsed moon would hear them and respond to their distress.”

By learning how to speak with nature, Alfi is beginning to bridge that divide between “human spaces and nature” that he notices earlier; that moment when he feels caught between skyscrapers and hills. Alfi started the walk with just an inkling of the wind through the brush in the Headlands, and he ends up discovering an ongoing dialogue with his surroundings. This kind of tuning in is the story’s attempt to put Ohlone knowledge in a modern context. In a sense, the Ohlone also embraced multiple intelligences, such as the idea that kids have different ways of learning. The Ohlone were great practitioners of experiential learning, believing teaching shouldn’t be just transferring information, but allowing young people to learn in their own ways. Thus Coyote never gives Alfi the answer to the vision. He lets him figure it out for himself. This indigenous method of instruction, with Coyote simply acting as a “guide to point Alfi towards nature's teachings,” has been developed in many outdoor education schools, including 4 Earth Elements education program, whose founder, Rick Barry, is an advisor to this project.

Presidio Visitor’s Center - Ohlone Scavenger Hunt

Right next to the tour site is the National Park Service’s Presidio Visitor’s Center. It’s full of history about the Presidio and contains some information on the Ohlone presence in the Presidio. This short scavenger hunt will help you find some of those Ohlone stories, history, and even items (like a real life Tule kayak!)

Get the PDF for the scavenger hunt here.

(And if you’re a parent or teacher the version with the answers in it is here.)

Classroom Uses

Discussion

Below are some suggested classroom activities both for before and after taking the tour.

For Younger children (6-9)

How does Alfi become like Mountain Lion?

What were some foods you think the Ohlone ate?

Helen isn’t mean, but what do you think is wrong with the way she was trying to teach Native American history?

What were some foods you think the Ohlone ate?

What did you like about the Ohlone way of life?

What didn’t you like?

For older children/adults

What challenges does Alfi overcome?

Does Helen’s village point out some problems with Minecraft?

How long has it been since the village of Petlenuc was here? (Answer: about 250 years)

What do you think is going to happen next to Alfi and Coyote?

You’re listening to the story from Alfi’s perspective, did you notice anything strange about how he hears the world?

Why do you think the Ohlone don’t live here any more?

What questions do you still have about the story?

Resources

Here is some further reading to learn more about Ohlone history and to integrate the tour into the classroom.

Classroom Curricula

Here is a list of classroom exercises and readings on Bay Area Ohlone and Miwok history and traditions.

A Short History of San Francisco

A wonderful book by professor emeritus of history at San Francisco State University, Robert Cherny, including well-written and up-to-date chapters on the Ohlone

Mission Dolores

Andy Galvan gives a great tour of the Old Mission Dolores that includes much Ohlone history and an Ohlone hut you step inside of.

The Ohlone Way

A great book that puts you in the shoes of the Ohlone when their culture was thriving throughout the Bay Area. Written by Malcolm Magolin a wonderful advisor and supporter of this project